The island of Fogo (fire) is a single giant volcano rising from the Atlantic Ocean. Once, it had been more than 4.000 m high, but 73.000 years ago its eastern flank collapsed into the sea, leaving a huge caldera at an altitude of around 1.700 m. Since then, regular outbreaks (at least one or two every century) created new volcanic cones inside the caldera, among them Pico de Fogo, with 2.829 m the highest mountain in Cape Verde, and it is said, that it might also be one of the steepest volcanos on the planet. In April 1995, an outbreak with a massive lava flow destroyed huge parts of the cultivated landscape as well as the road leading to Portela, the village inside the caldera, and its inhabitants had to be evacuated. The next outbreak in 2014 came with another lava flow that destroyed most of Portela as well as the neighbouring community of Bangaeira. But little by little, the people are coming back, building new houses amidst the black chunks of lava, frozen in time, and growing wine and fruits again. The soil is just too fertile to not use it.

Die Insel Fogo (Feuer) ist ein einziger riesiger Vulkan, der aus dem Atlantik ragt. Einst ist der über 4.000 m hoch gewesen, doch vor ungefähr 73.000 Jahren ist seine östliche Seite eingebrochen, ins Meer gestürzt, und zurück blieb eine gigantische Caldera auf etwa 1.700 m Höhe. Seither haben regelmäßige Ausbrüche (mindestens ein oder zwei pro Jahrhundert) neue Vulkankegel in der Caldera entstehen lassen, darunter der Pico de Fogo, mit 2.829 m die höchste Erhebung der Kapverden, von dem es heißt, dass er einer der steilsten Vulkane der Erde sei. Im April 1995 zerstörte ein Ausbruch mit seinem Lavastrom große Teile der Kulturlandschaft und die Straße, die durch die Caldera nach Portela führte, die einzige Siedlung, deren Bewohner evakuiert werden mussten. Der nächste Ausbruch 2014 brachte einen weiteren Lavastrom, der Portela und die Nachbargemeinde Bangaeira größtenteils zerstörte, aber Stück für Stück kehren die Menschen zurück, bauen neue Häuser mitten in und auf den eingefrorenen schwarzen Lavabrocken und bauen wieder Wein und Früchte an. Der Boden ist einfach zu fruchtbar, um ihn nicht zu nutzen.

Chã das Caldeiras (the caldera) is approached from the western side of the island on a road coming from São Filipe, and inside the crater, a newly built road is running along the foot of the steep cliffs bounding the caldera. As tourism plays a vital role on Fogo, some hotels had been among the first re-constructed buildings in Portela after the last outbreak. Among the few hotels, Casa Alcindo might be the nicest one, located right at the base of Pico de Fogo, but all the accommodations and the locals living up there are struggling with water scarcity. Freshwater is rare on all islands, but especially at Chã das Caldeiras on Fogo, where there is no natural water source. Another hardship in the crater can be the heat as the sun is burning down relentlessly on black volcanic rocks which heat up during the day and function as a radiator at night, so 30°C around midnight inside the hotel room (open windows, open door) might be, what you get when coming up there.

Nach Chã das Caldeiras (die Caldera) kommt man aus Richtung Westen auf der Straße von São Filipe, und in der Caldera führt die neue Straße am Fuß der steilen Kraterwände ringförmig bis nach Portela. Da der Tourismus ebenfalls eine tragende Rolle in der Wirtschaft Fogos spielt, waren Hotels unter den ersten Gebäuden, die nach dem Ausbruch wieder in Portela gebaut wurden. Unter den nach wie vor wenigen Unterkünften ist Casa Alcindo die vielleicht beste und charmanteste, direkt am Fuß des Pico de Fogo gelegen, doch alle Unterkünfte haben wie die Einheimischen dort oben mit Wasserknappheit zu kämpfen. Süßwasser ist auf allen Inseln ein rares Gut, aber in Chã das Caldeiras gibt es keine natürliche Wasserressourcen. Ein anderes Übel im Krater ist die Hitze, denn die Sonne brennt erbarmungslos auf schwarzes Vulkangestein, das sich tagsüber aufheizt und nachts als Heizung fungiert, so dass 30° C um Mitternacht im Hotelzimmer (bei offenen Fenstern und Türen) keine Seltenheit ist.

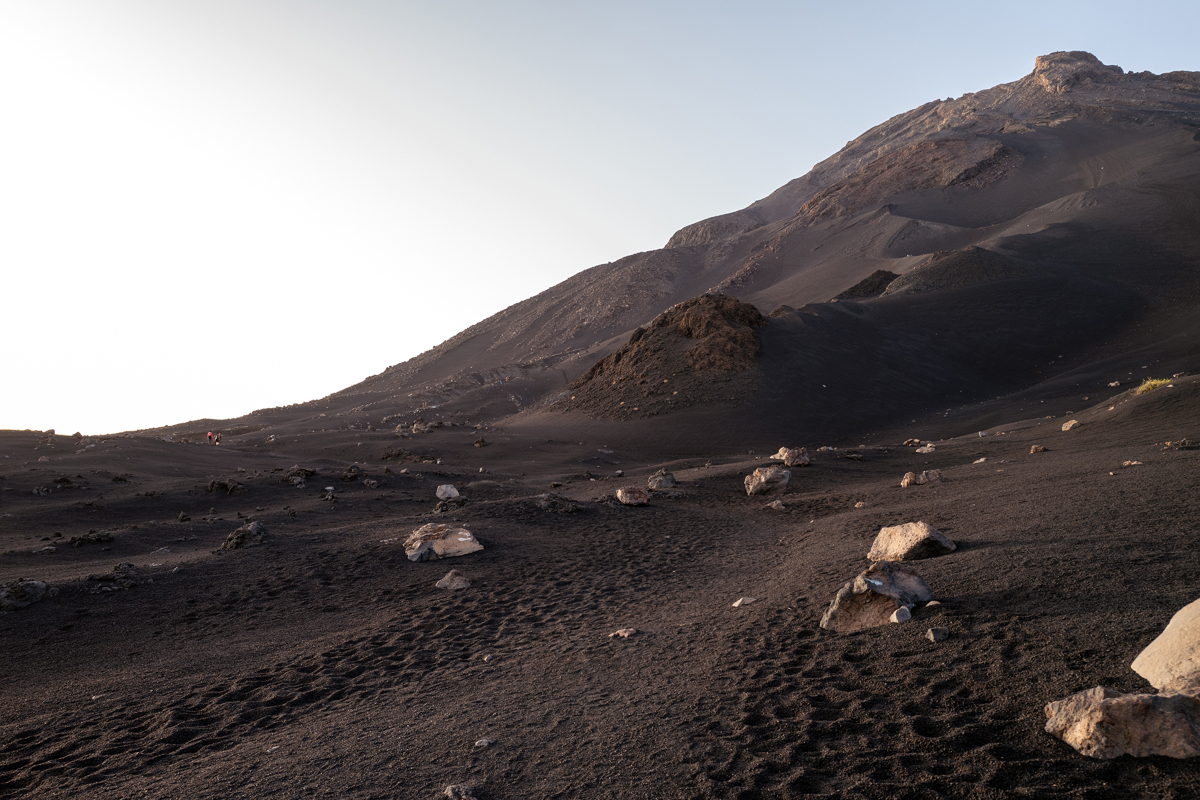

A Pico ascent starts early in the morning passing green vines on black soil, and with every step upward the wind is getting stronger and the air a little less hot and humid. It is a strenuous climb of at least three, three and a half hours (it might easily take you even four hours or more, depending on your fitness) up to the crater rim where you can smell the sulphur coming from various fumaroles. If you head westward and follow the Via ferrata circling the crater, you come to an extensive slope of black lava sand where it is safe to run down the volcano straight towards the crater from 2014 as well as the one from 1995, sticking out of Pico de Fogos western side. If you can ignore the razor-sharp crystalised lava sand quickly filling your shoes grinding your skin, it´s a truckload of fun running and sliding down this mighty slope.

Eine Besteigung des Pico startet früh am Morgen und führt anfangs vorbei an leuchtend grünen Reben auf schwarzem Vulkanboden. Schritt für Schritt steigt man höher, der Wind frischt auf, und die Hitze wird allmählich erträglich. Es ist ein äußerst anstrengender Aufstieg von mindesten drei, dreieinhalb Stunden (kann aber leicht auch vier Stunden oder mehr dauern, je nach Kondition) hinauf zum Kraterrand, wo man den Schwefel, der aus unzähligen Fumarolen austritt, riechen kann. Wer dann der Via ferrata, die den Krater umrundet, Richtung Westen folgt, gelangt an einen gewaltigen Hang mit schwarzem Lava-Sand, wo man die Flanke des Vulkans hinab zu den Kratern der Ausbrüche von 1995 und 2014, die aus der Flanke des Pico ragen, rennen kann. Wenn man die scharfkantige, kristallisierte Lava, die bereits bei den ersten Schritten die Schuhe füllt und die Haut abschmirgelt, ignoriert, ist es ein Riesenspaß.